The word profiling has been defined as the use of personal characteristics or behavior patterns to make generalizations about a person. Profiling is used in our everyday lives. When someone knocks on our door and we look through the peephole, we make a split decision on the person’s appearance to decide if we open the door or turn off our lights to show no one is at home. Dating sites and the internet collect data and use that information to present users with a compatible person or products. However, profiling is not limited to just people. Think about walking along the sidewalk and you see a pit bull (no offense to pit bulls).

Some of us may be intimidated and decide to walk across the street. Or you go to the supermarket, and the closest parking space is next to a car with big doors or has lots of dents. You may decide to park a little farther to keep your car dent free.

In oncology, profiling has been around for quite some time. A good example is estrogen receptors for breast cancers. In 1896, it was noted that removal of ovaries in premenopausal women with advanced breast cancers led to regression of their cancer. However, only about 30% of women responded after removal of the ovaries. Even though this relationship between estrogen and breast cancer was known, it was not until the mid-1970s when a test was developed by breast cancer researchers to detect estrogen receptors on cancer cells that allowed them to respond to estrogen ablative therapies. As a standard of care, all breast cancers are tested for these receptors to determine if they will benefit from removal of the ovaries to taking a pill for the next five to ten years.

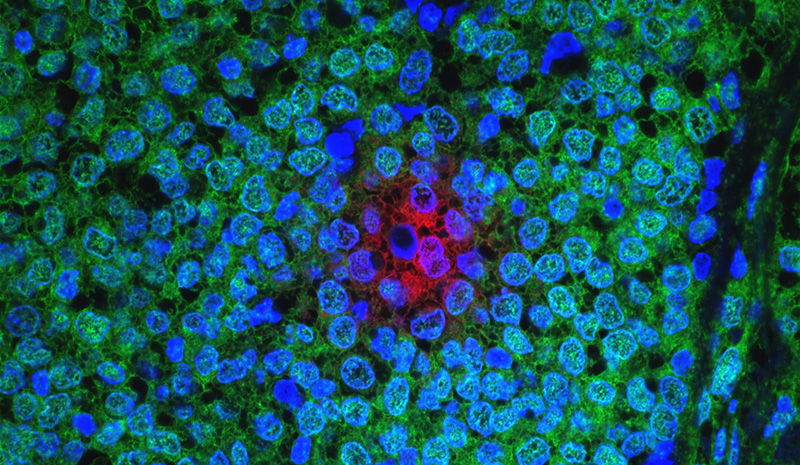

Much has changed since 1970. With advances in medical knowledge and technology, profiling has extended beyond testing for hormone receptors. Profiling now looks at the mutated genes of the tumor cells. These genes instruct cancer cells to grow, to spread, form blood vessels, become more aggressive, and hide from the body’s immune system. By understanding the behavior of these mutations, we can apply appropriate targeted and molecular therapies.

A widely-used test to profile breast cancer is the Oncotype DX. By analyzing 21 genes, this helps the oncologist determine if an early-stage breast cancer is harboring aggressive behavior to spread, (what I call a wolf in sheep’s clothing), and would benefit from chemotherapy. For all cancers, profiling can provide the physician with gene-specific information about the tumor and can assist in deciding which chemotherapy drugs could be most effective against them. Some mutations allow a cancer to hide from the body’s immune system. Profiling can detect these mutations and allow the oncologist to use immunotherapy drugs to “unmask” these tumors and allow the body’s own immune system to target the tumor.

In summary, most cancers are best treated by standard of care guidelines. For now, molecular profiling can provide information to your oncologist regarding the necessity of chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. In instances of rare cancers or those that have not responded to standard cancer treatments , profiling can aid the oncologist in choosing the best therapy for that cancer.

Robert Gin, MD, is a Radiation Oncologist at Arizona Oncology in Tucson. He received Bachelor of Science degrees in Chemistry as well as Molecular and Cellular Biology, with a minor in math and physics, from the University of Arizona, where he also completed his residency in Radiation Oncology, serving as Chief Resident.